Heart Rate Training for Runners

print

article

Introduction

Using heart rate as an alternative to pace is a popular choice with many runners, and it comes with a range of benefits.

However, to get the most out of heart rate training, it's essential to understand when it's useful, when other methods might be more appropriate, and how to determine critical metrics such as your resting and maximum heart rates and personal heart rate training zones.

This evidence-based guide uses the latest research to tell you everything you need to know to make the most of heart rate training. We also review some sample training sessions, discuss common approaches and methods, and dispel frustratingly persistent myths.

Benefits of training by heart rate

The most attractive feature of using heart rate to train is that it provides a direct and objective measure of intensity during exercise. Other things being equal, the harder you run, the higher your heart rate. This strong correlation between heart rate and expended effort means that you can be confident that you're hitting the correct intensities during your training sessions and getting the most out of them.

Modern equipment, software, apps, and online tools allow you to easily monitor heart rate while running and to carry out in-depth post-session analysis.

Heart rate vs. perceived effort

Perceived effort/exertion (PE) is a subjective measure that simply involves considering how hard it feels to perform an activity. It involves assessing a combination of factors, such as heart rate, breathing rate, muscle fatigue, and desire to stop running. All these factors considered together produce a score that represents the overall difficulty.

Don't worry if that sounds far too formal and complicated; for practical purposes, you only need to ask yourself: "How hard does this feel?" You don't even need to assign a score to an effort; you can simply measure each run relative to other runs. Many runners are happy speaking and training in terms of easy, easy, moderate, and hard runs.

Perceived exertion and the Borg scale

A standardized means of measuring perceived exertion is the Borg Rating of Perceived Exertion (RPE) scale1, established by Swedish researcher Gunnar Borg in his 1998 book Borg's Perceived Exertion and Pain Scales2.

RPE scores3 can vary from a minimum of 6, equivalent to no exertion at all, to 20, which is maximal exertion.

The keen-eyed reader may note that if the scale's values are multiplied by ten, they suggest a typical heart rate range. I.e., a resting heart rate of 60 and a max of 200. This is a feature of the scale rather than an accident. Although it obviously only works for a specific heart rate range.

Borg also developed a Category-Ratio (CR-10) scale. CR-10 scores4 vary from 0 (no exertion) to 10 (maximal exertion). This scale is often used to measure pain intensity, as well as exercise intensity.

The benefits of perceived effort

A sound argument can be made for training according to perceived effort. It's certainly true that more-experienced runners are able to identify the intensities they should be hitting during training sessions and judging how tired they should expect to feel after different types of runs.

Running by effort also has the benefit that it's unnecessary to continually monitor heart rate or pace or worry about whether a particular reading is a spike or an anomaly. In fact, a significant benefit of PE is that it requires no equipment whatsoever.

The drawbacks of perceived effort

Whether to use heart rate or perceived effort is primarily personal preference. However, remember that when you're running according to effort, it's easy to overdo it if you're feeling particularly good or during the earlier reps in an interval session when you're still feeling fresh.

Beginners and less-experienced racers can struggle to judge intensity during races. And even advanced runners sometimes find it difficult.

Linking heart rate and perceived effort

It can be handy for all runners to learn to match heart rate readings to intensities. E.g., one runner might note that a moderately hard run is usually in the 160–170 bpm range. I've found that an excellent way to learn which heart rates match which intensities while running is to guess a heart rate before looking at the reading on your watch. Over time, your judgment will improve significantly, and you'll barely need to look at your watch.

Heart rate vs. pace

The benefits of pace

Ultimately, runners are concerned with their pace during races, so a strong argument can be made for training according to pace. Spending time at race pace is an essential element of all training regimes (and one that's often overlooked).

Heart rate can be misleading in the earlier stages of a run or a race since it will take a while to rise to a level indicative of the average intensity. This problem can be mitigated with a thorough warm up5, bringing your heart rate closer to the run or race average. But keeping an eye on pace until heart rate catches up is a sensible approach.

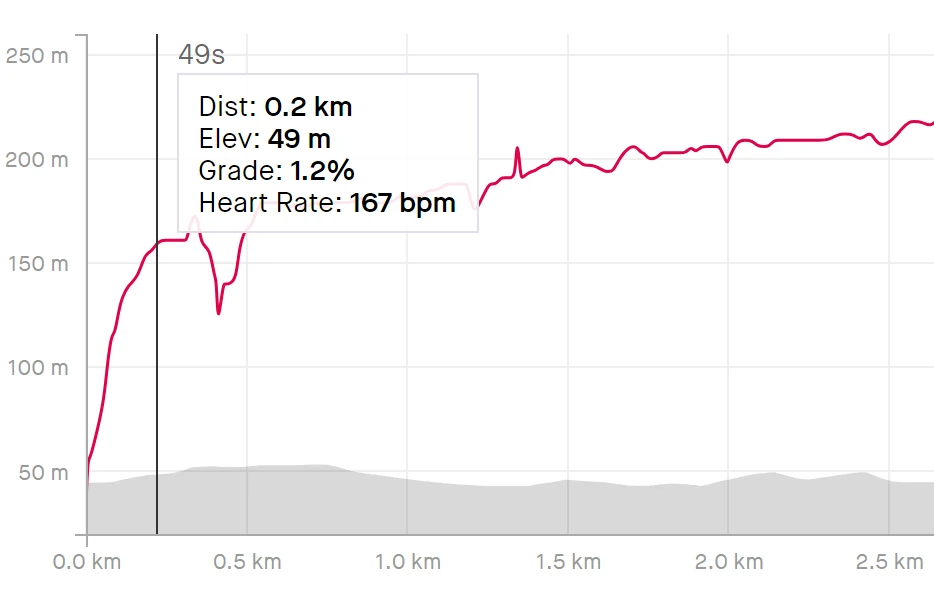

As a real-life example, the image below shows my heart rate profile during the first 2.5 km of a 5k race. My heart rate climbed quickly for the first 0.2 kilometers (200 meters) before switching to a more gradual rise, which continued throughout the rest of the race. For context, my maximum heart rate is 202 bpm, my average heart rate for this race was 188 bpm, and it peaked at 198 bpm towards the end.

Note also the sudden drop in heart rate at about 0.4 km. This is an anomalous reading that is resolved about 100 meters later. The lesson here is to not put too much trust into any single reading.

During a race, excitement, adrenaline, and the presence and speed of other runners can make judging effort very difficult, particularly in the earlier stages, so we strongly recommend closely monitoring your planned pace and sticking to it.

The drawbacks of pace

Pace is an inferior measure of intensity on hilly runs: a pace that requires a monumental effort to achieve on an uphill run can feel like a gentle jog on a downhill. And even minor gradients can be misleading. Temperature, heat, terrain, and hydration can also significantly affect the work required to maintain a particular pace.

When recovering from illness or returning to running following a break, heart rate, as opposed to pace, is a valuable way of ensuring you aren't working harder than may be appropriate.

Linking heart rate and pace

A key indicator of improved fitness is noting a lower heart rate during exercise.

Observing the pace achieved for a particular heart rate, or vice-versa, provides an excellent means of monitoring progress that can be carried out far more often and requires much less recovery than assessing fitness according to a race result. Periodically completing the same route at the same heart rate and noting a drop in pace indicates an improvement in fitness. Alternatively, running the same route at the same pace and seeing a reduction in heart rate also shows that fitness is improving.

Racing by heart rate

If you have a specific target for a race, your plan is probably to run according to pace rather than by effort or monitoring your heart rate. However, using heart rate as an alternative to pace can be extremely useful in certain situations:

- After a break from training. If you're uncertain about fitness levels, using heart rate as a guide can ensure you don't misjudge your race effort.

- If you're feeling less than ideal on race day for any reason. For example, if you've been suffering from a cold or sleeping poorly.

- For hill races. Pace is a poor guide for these races. Heart rate monitoring can ensure an even effort, regardless of course elevation.

- In unexpected conditions. If it's very hot or windy on race day, keeping an eye on your heart rate can ensure you don't overexert yourself.

For these reasons, we recommend that all runners become familiar with their personal heart rate ranges for various race distances. You don't need to carry out an advanced analysis; you can simply look at your heart rates for any recent races and keep a record of these.

I've done this before. For example, here's my informal race plan for a half marathon when I had been injured for a few weeks in the lead-up to the race and hadn't had a chance to get in any longer runs.

Half marathon race plan

(Max HR: 202)

- Mile 1: Run by feel. Keep things gentle.

- Miles 2 to 4: Keep heart rate below 170 bpm

- Miles 4 to 7: keep heart rate below 175 bpm

- Miles 7 to 10: keep heart rate below 180 bpm

- Miles 10 to finish: run by feel

I was able to take this approach because I have a lot of heart rate data from past races. Note that I ran by feel during the first mile of the race. This is because, as explained above, heart rate takes a little while to climb after starting a run, so it is a poor guide for the first few minutes. I also decided to run the final 5k according to perceived exertion since I knew I'd have a good idea of what I could sustain by this point in the race.

Resting Heart Rate

Your resting heart rate (RHR) is the number of beats recorded per minute when completely relaxed while sitting or lying down. Resting heart rate is typically between 50 and 90 beats per minute (BPM)6.

Factors affecting resting heart rate

Your resting heart rate can vary according to a variety of factors:

- Genetics. Resting heart rate is a heritable trait7.

- Sex. The mean resting heart rate for men is 64 and the mean for women is 678.

- Age. Resting pulse rate decreases with age9, peaking for men in early adulthood and for women in middle age.

- Medication. Certain medicines, such as beta-blockers10, can slow the heart. Others can speed it up.

- Stress. Both physical and emotional stress can cause heart rate to increase11.

- Stimulants. Some of these fall under the umbrella of medication, but caffeine12 and nicotine13 are common stimulants that can affect heart rate.

- Alcohol. Although officially a depressant, alcohol has stimulant properties that can increase heart rate14.

- Hydration. Dehydration results in less fluid in the blood, which means heart rate increases to compensate15.

- BMI. A higher BMI is associated with a higher resting heart rate16.

- Sleep duration. A lack of sleep typically results in an increased resting heart rate of a few beats per minute16. Oversleeping can also result in an increased resting heart rate. The lowest values seem to be achieved when seven or eight hours of sleep is taken.

- Fitness. Fitter individuals will generally have a lower resting heart rate17.

Some of these are outside your control. However, it can be interesting to note the benefits of reduced stress and stimulant use, improved hydration, weight loss, better sleep, and improved cardiovascular fitness by observing a decrease in resting heart rate alongside changes in these factors.

Measuring resting heart rate

- Ensure you are well rested and hydrated, not overly stressed or anxious, and haven't overindulged in food, coffee, nicotine, or alcohol the day before.

- Take any medication as directed. But if you're taking medication in the short term, it may be best to wait until you've completed the course before carrying out the test.

- Take the measurement immediately after waking up while still lying down.

- Use your index and middle finger to locate your pulse in your neck (between your windpipe and jaw) or your wrist (at the base of the thumb below the palm of the hand).

- Start your timer and count the number of beats in one minute. This is your resting pulse rate.

- Take a reading on the following day to ensure that the first is not out of the ordinary. If the measurements differ by more than a few beats per minute, then one or both readings may be unrepresentative, so continue to measure each morning until the values on consecutive days are similar.

Maximum Heart Rate

Your maximum heart rate (MHR) is simply the highest number of beats per minute that your heart can produce.

There is a widespread misunderstanding that maximum heart rate in the context of exercise refers to a value above which you should not train. For example, I once coached a runner concerned that she had been training above her "maximum." This confused me because if your heart rate can go above a particular value, that value obviously isn't your maximum. It transpired that she had estimated her max HR using a dreaded formula, which was suggesting a value about 20 beats per minute lower than her true maximum. She incorrectly assumed, as it appears many do, that this value was a limit and that exceeding it could be unhelpful or harmful.

Factors affecting maximum heart rate

Maximum heart rate is affected by fewer factors than resting heart rate and is far less variable.

It's well understood that maximum heart rate decreases with age18, and this is the basis for many of the formulas that have been suggested (see below). However, there is evidence that maximum heart rate can decrease with training19 by as much as 13 beats per minute.

Maximum heart rate formulas

Several formulas are available for estimating maximum heart rate based on age and sex. However, although, as a general rule, it will decrease as you age, it varies wildly within the population, and none of these formulas is reliable. If you rely on a calculation to determine your maximum heart rate, there is a strong possibility that it will be incorrect and that you will end up training sub-optimally. Unfortunately, it is still very common, even amongst otherwise respectable and reliable organizations, to prescribe exercise according to an age-based formula.

For interest's sake you may wish to compare your actual maximum heart rate with what the most popular formulas predict20. However, you should ignore any training advice or prescriptions based on values determined via a formula.

The most well-known and popular formula is the memorable 220 − age. As an example of how inappropriate this is, my age at the time of writing is 46, and I have measured a heart rate of 202 bpm on a few occasions within the last year. If I were to rely on the 220 − age formula, I would assume a max of 174bpm. This would mean I'd be doing my threshold runs at about 160 bpm, whereas my actual lactate threshold is around the 185 bpm mark. The Journal of Exercise Physiology has an interesting article on the history of the 220 − age formula21.

Measuring maximum heart rate

The best way to determine your true maximum heart rate is to conduct a field test. There is no standard protocol for determining maximum heart rate22, but evidence suggests appropriate warm-up times, duration and number of repetitions performed, and treadmill inclination23. Unfortunately, it is not possible to reliably and accurately estimate maximum heart rate from submaximal tests24, which means that any method used requires an element of maximal effort.

The advice and protocols presented here are based on this evidence and personal experience coaching athletes of various abilities.

Maximum heart rate test requirements

Before you carry out the test, ensure that:

- You're medically fit and of sound health. Seek professional advice if unsure.

- You aren't suffering from any illnesses.

- You aren't carrying an injury.

- You're well rested. It's best to have had a day or two of rest before the test.

- You're mentally prepared for a respectable effort.

- You're well warmed up. At least 20 minutes of easy running is necessary.

Also, be wary of the data from any heart rate monitors you use. The latest models are good but can occasionally suffer from spiking. That is, they sometimes report high heart rates that did not occur. However, it should be easy to determine where these spikes occurred by examining the data post-run. Here are some tips to avoid spiking25.

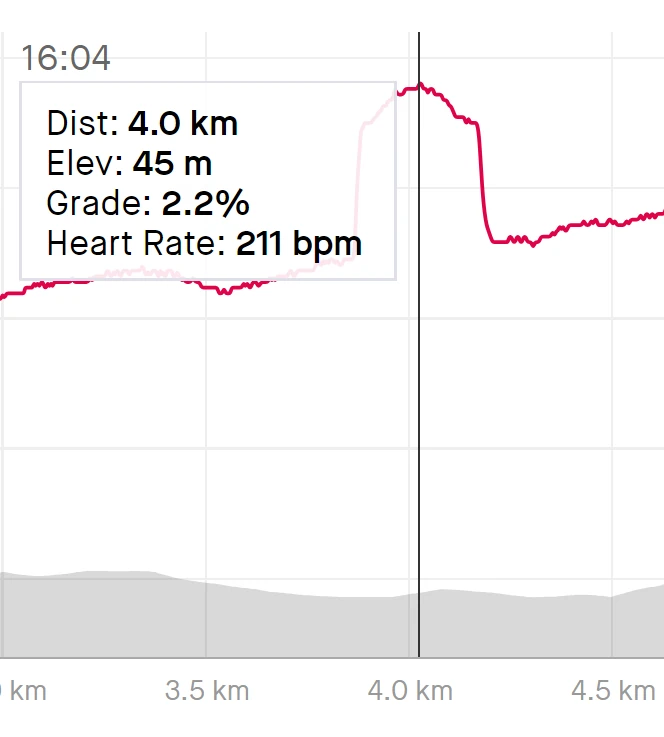

Below is a real example of a heart rate spike I experienced during a 5k run. My heart rate was hovering around 180 bpm, then suddenly jumped to around 210 bpm (which is actually 8 bpm above my maximum, as measured separately). It stayed there for about a minute before returning to around the 180 bpm mark again. This particular example shows that spikes aren't necessarily "spiky."

If you don't own a heart rate monitor, you can count your pulse for 15 seconds immediately following the effort and multiply the result by four to get your beats per minute. Limiting the duration of the count to 15 seconds is best since your heart rate will start to drop as soon as you stop running, making measurements over longer durations unreliable.

Below are four options for conducting a maximum heart rate test in the field. Any of these methods should get you close to your maximum. For training purposes, the odd beat or two isn't going to make a significant difference, so don't be overly concerned about achieving an exact measurement.

Method 1: the race

This approach involves wearing a heart rate monitor during a race and noting the highest heart rate achieved.

This works best if the race lasts between 20 and 45 minutes. During shorter races, your heart rate may not have a chance to reach its maximum. And during longer races, the intensity may not be high enough. Although "eyeballs out" efforts at the end of longer races can see heart rates reaching their maximum.

Method 2: the track

This doesn't have to take place on a track, but it can be a useful way to measure distances and convenient for runners familiar with a track environment. The focus here is really on the distance you're running.

- 2–3 mile warm up. Start at a jogging pace and finish at a moderately hard intensity.

- Three 100m strides26 (90&prcnt; of top speed) with walk-back recovery.

- 1600 meters at between 5k and 3k pace.

- Directly following the 1600 meters, run 400 meters flat out.

Method 3: the hill

A hill is not essential, but it may help you push yourself. The focus here is on the amount of time you're running.

- 20-minute warm-up. Start at a jogging pace and finish at a moderately hard intensity.

- Three sets of 20-second strides26 (90&prcnt; of top speed) with walk-back recovery.

- Run six minutes hard, at close to the limit of what you are able to sustain for this time.

- Directly following the six-minute effort, run as hard as possible for one minute.

Method 4: the treadmill

This approach involves periodically increasing a treadmill incline until your heart rate stops rising.

- 25-minute warm-up. Start at a jogging pace and finish at a moderately hard intensity.

- Set the treadmill speed to one you feel you could maintain for about 20 minutes.

- Increase the treadmill incline by 1% every minute.

- Continue running until exhaustion.

Heart Rate Reserve

Your heart rate reserve (HRR) is simply the range throughout which your heart beats. I.e., from your resting heart rate up to your maximum heart rate. It can be helpful to consider it your working heart rate or heart rate capacity.

Heart Rate Reserve = Maximum Heart Rate − Resting Heart RateUsing your heart rate reserve, rather than your maximum heart rate, to design heart rate sessions, has been shown to be a superior method27. This is reflected in the switch by the American College of Sports Medicine28 from using maximum heart rate for exercise prescription to using heart rate reserve in 199529.

Heart rate reserve is better because your resting heart rate will vary according to your level of conditioning, decreasing as your fitness improves. So, as you grow fitter, your heart rate capacity grows. Runners with the same maximum heart rate but different resting heart rates, and therefore different heart rate reserves, will have different heart rate training requirements.

Heart Rate Zones

Heart rate zones are simply a way of describing ranges of intensities. A zone specifies a minimum heart rate and a maximum heart rate, and any running performed between these two values counts as running within that heart rate zone. The basic idea is to train within certain zones to achieve a desired training effect.

Determining heart rate zones

There are two methods of determining heart rate zones:

- By using percentages of your maximum heart rate. Here, each zone's upper and lower bounds correspond to a percentage of your maximum.

- By using percentages of your heart rate reserve, which can be calculated from your maximum and resting heart rates. Here, each zone's upper and lower bounds correspond to a percentage of your heart rate reserve.

Choosing the zones

The percentages chosen for each zone's lower and upper boundaries will vary according to the researcher or coach. The zones we have chosen are based on published research30 and personal experience with various athletes. Despite this approach, it is impossible to derive a general rule for every type of runner. However, the beauty of dealing with a range of heart rates, rather than with a specific value, is that those values in the middle of each range are exceptionally likely to work well for almost everybody. It's only really at the lower and upper boundaries of the zones where runners will be in danger of training in the wrong area. And even then, the effect will be small.

We have chosen to present five main training zones that are calculated according to either maximum heart rate or heart rate reserve.

The calculation for the maximum heart rate approach simply involves multiplying a percentage value by the maximum heart rate:

Heart Rate Zone = Maximum Heart Rate × PercentageFor the heart rate reserve approach, we multiply by heart rate reserve and then add on resting heart rate.

Heart Rate Zone = Heart Rate Reserve × Percentage + Resting Heart RateLooking at the Karvonen method helps explain this logic.

The Karvonen formula

The Karvonen formula31 is a way of determining exercise intensity, expressed as a percentage of heart rate reserve:

HRR% = (HRtrain − HRrest) ÷ (HRmax − HRrest)Where

HRR%is a percentage of heart rate reserve,HRmaxis maximum heart rate,HRrestis resting heart rate, andHRtrainis a particular training heart rate.

This basically says that if we know a person's maximum and resting heart rates and the heart rate they're running at, we can calculate a heart rate reserve percentage.

We can rearrange the Karvonen formula to put HRtrain on the left-hand side. This gives us:

HRtrain = (HRmax − HRrest) × HRR% + HRrest

This allows us to specify the heart rate value corresponding to a heart rate reserve percentage based on an individual's maximum and resting heart rates.

Luckily, you don't need to do this manually. You can use our heart rate zones calculator33 to quickly find your personal zones by plugging in your resting and maximum values. Our calculator works for both the maximum heart rate method and the heart rate reserve method.

Zone ranges and descriptions

The table below shows target heart rate zones and the ranges of percentages of maximum heart rate (MHR) and heart rate reserve (HRR) that correspond to each zone.

| MHR Range | HRR Range | Description | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Zone 1/Light

|

< 68% | < 60% |

Zone 1/Light

< 68% MHR

< 60% HRR

Zone 1 includes very light exercise, usually reserved for early on in a warm-up or for short recovery runs. Some coaches consider exercise at this intensity to constitute "junk miles".

|

|

Zone 2/Aerobic

|

68–81% | 60–75% |

Zone 2/Aerobic

68–81% MHR

60–75% HRR

The bulk of training should take place in zone 2. This zone is suitable for general aerobic conditioning and improving endurance. Zone 2 is sometimes called the fat burning zone since it's often believed you will burn fat most efficiently when running within this range of intensities, but it's more beneficial to include separate zones for fat burning. This zone is also suitable for long runs, warm-ups, and cool-downs.

|

|

Zone 3/High aerobic

|

82–86% | 76–83% |

Zone 3/High aerobic

82–86% MHR

76–83% HRR

Training within zone 3 will improve aerobic capacity by strengthening the cardiovascular and peripheral systems, promoting increased vascularization, meaning a greater blood and oxygen supply to muscles. This zone is also a great alternative to zone 2 when you're feeling particularly good.

|

|

Zone 4/Anaerobic

|

87–93% | 84–91% |

Zone 4/Anaerobic

87–93% MHR

84–91% HRR

Zone 4 covers intensities from just below to just above your anaerobic threshold (the middle of this zone is roughly the intensity you could maintain for an hour in a race situation). Training in this zone can help raise your anaerobic threshold, meaning you can run harder and faster at both this and other intensities.

|

|

Zone 5/Red Line

|

94–100% | 92–100% |

Zone 5/Red Line

94–100% MHR

92–100% HRR

This is the zone that is used for interval training. Training in this zone will help train your fast twitch muscle fibers and raise your VO2 Max. This type of training should be limited.

|

|

Fat Burning Zone: Men

|

58–74% | 50–70% |

Fat Burning Zone: Men

58–74% MHR

50–70% HRR

This is the heart rate range for men within which calorie burn from fat will be optimized. Note that the optimal range for men is slightly lower than women's.

|

|

Fat Burning Zone: Women

|

60–79% | 52–74% |

Fat Burning Zone: Women

60–79% MHR

52–74% HRR

This is the heart rate range for women within which calorie burn from fat will be optimized. Note that the optimal range for women is slightly higher than men's.

|

Fat Burning Zones

A common claim is that running in heart rate zone 2 is the most efficient way to burn fat while running. For this reason, zone 2 is often called the "fat-burning zone." However, this isn't quite correct. Although there is an overlap, the heart rate ranges that burn fat most efficiently30 differ from the zone 2 ranges.

Fat-burning zones are also slightly different for men and women, with women burning fat more efficiently at somewhat higher heart rates than men.

This is why, in addition to the standard five zones, we have included two extra fat-burning zones: one for men and one for women.

The table below summarizes calorie burn for men and women running in the fat-burning zone (adapted from the original33).

| Men | Women | |

|---|---|---|

| Total cals / min | 7.6–12.5 | 5.6–9.6 |

| Fat cals / min | 3.7–4.3 | 2.4 |

The appeal of such a zone is clear for those trying to lose weight, but there are a couple of points to remember if weight loss is your goal.

The first is that although the fat-burning zone is where the ratio of calories burned from fat to overall calories burned is highest, absolute calorie burn is proportional to intensity, so you will burn more calories overall for more intense exercise.

To illustrate this point, compare a runner working at 68% of their maximum and a runner working at 87% of their maximum (which are the lower and upper bounds of zone 2 and zone 3 aerobic zones):

| 68% MHR | 87% MHR | |

|---|---|---|

| Total cals / min | 9.2 | 3.1 |

| Fat cals / min | 14.2 | 1.7 |

| % cals from fat | 34 | 12 |

It's clear that while the proportion of calories from fat is higher for the lower intensity, the overall calorie burn is more significant for the higher intensity.

The second point to consider is that there is some evidence that High-Intensity Interval Training (HIIT) is superior to other types of exercise for fat reduction34.

These points suggest that a runner seeking greater overall calorie burn should target higher intensities. But this needs to be balanced against the fact that longer can be spent running at lower intensities, and recovery will be quicker, so both the duration of individual runs and overall training volume can be more significant by spending a lot of time running in zones 1 and 2.

This is all in danger of becoming bewildering for the runner trying to lose weight using heart rate zones. The best recommendation is probably similar to that for those who are training for performance, and to carry out most of your training in the lower zones, but to also include training sessions that hit the higher zones, including interval sessions such as HIIT, since they can bring about various other benefits, both in terms of training effect and body composition changes.

Zone 1 and junk miles

Zone 1 running dictates an intensity below 68% of maximum heart rate or 60% of heart rate reserve. Some coaches would place this slower running into the category of "junk miles." That is, miles run so slowly that they don't improve fitness but just contribute to breakdown and fatigue.

This assertion is strongly contested by other running coaches, and training at lower aerobic levels can indeed elicit fitness improvements.

The correct perspective is that "it depends." Running in zone 1 is better than doing nothing (assuming a rest isn't required), but running all your mileage in zone 1 won't be as beneficial as including running in a mix of zones.

My suggestion is that zone 1 running is an excellent alternative to zone 2 running if you're in the mood for something gentle. Conversely, if you're feeling particularly good, zone 3 is an excellent alternative to zone 2.

Heart rate running sessions

Zone training

Zones 1, 2, and 3

For extended runs in zones 1, 2, and 3, we suggest starting the run towards the lower end of your target heart rate zone and gradually progressing to the upper end of the zone. For interval and repetition sessions using heart rate, we suggest that the first rep be carried out at a heart rate towards the lower end of the zone; for each subsequent rep, the heart rate should be allowed to increase a little, with the final rep occurring towards the upper end of the zone. This approach fits well with the natural tendency for heart rate to climb during prolonged exercise, known as cardiac drift36.

Our heart rate zones calculator32 not only calculates your personal zones but also generates sample zone 3, 4, and 5 sessions for you. Here are some examples generated by the calculator based on my maximum heart rate of 202 bpm and my resting heart rate of 52 bpm.

Zone 3 session example

Max HR: 202; Resting HR: 52

Zone 3 HR range: 166 bpm–177 bpm

30 minutes @ 166 bpm

5 minutes @ 177 bpm

20 minutes @ 166 bpm

5 minutes @ 177 bpm

20 minutes @ 172 bpm

Zone 4 session example

Max HR: 202; Resting HR: 52

Zone 4 HR range: 178 bpm–189 bpm

15 minutes @ 178 bpm

5 minutes easy

15 minutes @ 184 bpm

3 minutes easy

5 minutes @ 189 bpm

Zone 5 session example

Max HR: 202; Resting HR: 52

Zone 5 HR range: 190 bpm–202 bpm

2 x 4 minutes @ 190 bpm with 2 minutes jog/walk between reps

2 minutes jog

3 x 3 minutes @ 196 bpm with 90 seconds jog/walk between reps

Session suggestions

Our sessions35 page has examples of runs you can perform using heart rate, such as one that involves using heart rate to pace yourself on a hilly run37 and another that involves progressively increasing the intensity of a run by monitoring heart rate38.

Heart rate recovery

Heart rate recovery is the rate at which your heart rate decreases following exercise. It's usually measured in beats per minute per minute. For example, a runner who recorded a heart rate of 185 immediately following exercise, and then a heart rate of 170 one minute after exercise would have a heart rate recovery of 15 beats per minute.

A typical heart rate recovery for healthy adults is between 12 and 23 beats per minute39.

Heart rate recovery is a popular measure of cardiovascular fitness. It tends to be slower in older people and faster in those who are well-trained40.

Many running watches display your heart rate recovery when it's assumed an effort has finished, typically two minutes after stopping your watch.

Heart rate variability

Heart rate variability (HRV) refers to the variation in time between individual heartbeats.

These variations are slight, so they are not usually noticeable without the use of equipment such as a heart rate monitor.

A high HRV is usually associated with younger age, stress resilience, and greater cardiovascular fitness41, but it can also indicate health problems42.

Understanding and tracking your HRV can be a valuable way of measuring changes in fitness and identifying possible health concerns.

Heart rate training methods

Low heart rate training

Low heart rate training involves carrying out most or all of your running at a low aerobic intensity.

The idea is that by reducing the intensity of your training, you can increase the overall volume without overtraining. This is because not only can each run be longer, but you will recover more quickly.

Low heart rate training plans can be very effective. However, running coaches seem to prefer them to runners. We suspect this is because although low heart rate training programs look good on paper, they can be very, very dull for the athlete actually doing the running. A runner who persists for a little while will eventually be able to run faster on their easy runs, but it certainly requires a bit of patience at first.

Popular low heart rate training systems include those developed by Phil Maffetone and Joe Hadd.

Maffetone

Phil Maffetone's method begins with his MAF 180 formula: first, subtract your age from 180, then deduct further points according to various health and well-being factors. The resulting value is used to dictate the intensity of training sessions.

While the principles of training at a low heart rate are sound, Mafettone's formula is not. We explained above why formulas should not be used to find maximum heart rate or to prescribe training, and there is nothing different about the MAF 180 formula. If you are keen on following Maffetone's plan then we suggest you adjust for the erroneous formula by calculating your HR age.

Your HR age is your age according to the 220 − age formula. If we rearrange:

max HR = 220 − age

to put age on the left-hand side:

age = 220 − max HR

You can now plug your HR age, instead of your actual age, into the MAF 180 formula:

180 − HR age

With a more realistic value available, you can embark on your MAF training journey with greater confidence. You can read more about the Maffetone system on his website43.

Hadd

John Hadd's approach to training was detailed in posts on the Let's Run44 message boards in 2003, have disappeared now. The basic idea is that muscle adaptation is optimized by training in aerobic zones, and a runner's lactate threshold is raised. There is an archive of a site available that has compiled the various posts in one place45.

Heart rate monitors

Traditionally, heart rate monitors have required the use of a chest strap. However, watches with built-in optical heart rate sensors are now fairly standard.

Although the watch-only option is more comfortable, and most have the benefit that they provide the opportunity for continuous heart rate monitoring outside of training sessions, chest straps tend to be more accurate than wristband sensors46. Evidence also suggests that wrist-worn devices are less accurate for those with darker skin tones47.

I prefer a chest strap since I've found that my Garmin Vivoactive 448 really struggles to measure my pulse rate once my wrist gets sweaty. But if you're looking for in-depth analyses of running watches and their features, I recommend DC Rainmaker's product reviews49.

Whichever you choose, both provide real-time monitoring, and apps and websites such as Garmin Connect50 and Runalyze51 make for easy post-run analysis.

Many watches and their accompanying software also allow you to specify your heart rate zones and display the zone as you run.